This started out as a quick list with photo examples to check chisels against when discussing them. Upon writing the first couple of sentences it morphed into a far more detailed article.

I’d like to thank Bob Smalser, as this reference was originally based off his article. Additional references cited in-line. I’ve learned a bit in writing this and no doubt will continue to discover information on chisel types. Revisions will be made accordingly.

I’d like to note the terminology of chisels is both flexible and varies over time and region. Around the turn of the 20th century, American catalogs largely agreed on terminology but carried different ranges. I’ve read plenty of vintage and contemporary instructional woodworking literature that is much more liberal with its usage.

Illustrations are chosen from period catalogs because I find them easier to view and more consistent. Sources are noted in the captions and links can be found at the bottom of the page.

Most terminology that applies to chisels also applies to gouges. A specific section for details unique to gouges is forthcoming.

All bevels are +/- 5° or so. In some cases, the only substantive difference between one kind of chisel and the other is the bevel. This is by no means a rule-book on bevel angles or chisel usage. Your blades, your work, your discretion. Blade length is measured as in the following image:

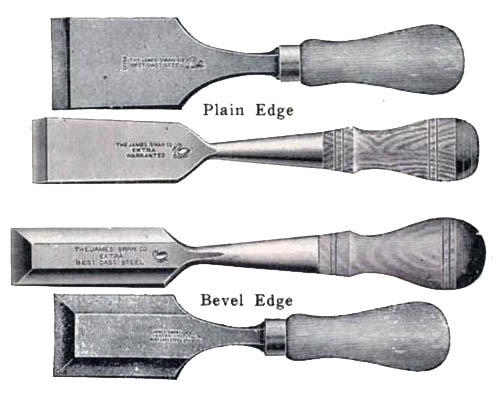

Handles come in a great variety on chisels. Numerous styles were available and many owners chose to make their own. Here’s a sampling of styles offered by manufacturers:

Chisel types

Firmer

I’ve started with firmer for a reason. The use of ‘firmer’ really describes the construction of chisel rather than a specific application. Almost any any chisel or gouge could be made and then described as ‘firmer’.

The term ‘firmer’ refers to the manner in which the tool is made and the material out of which it is made. Firmer chisels have blades wholly out of [cast] tool steel, while in some kinds of chisels iron blades overlaid with steel [cutting edges] are used.

–Park, pg. 40 1

That quote suggests that ‘firmer’ may have come about because they are stiffer/stronger than laminated chisels.

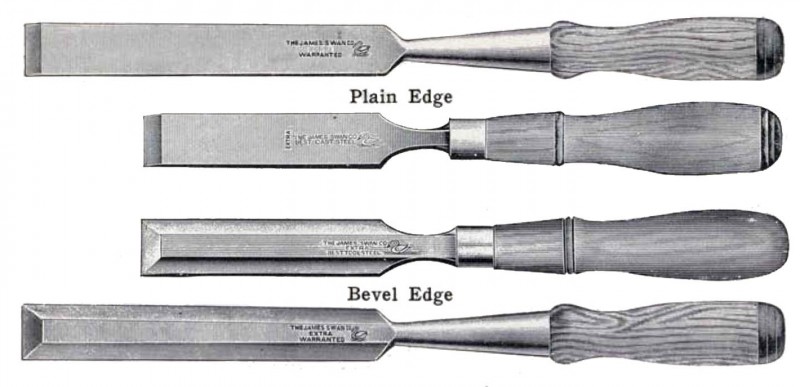

In some catalogs firmers are also thicker than regular chisels, if offered, but this is not universal. They can have sockets or tangs and vary to every length. Swan offered firmers in Butt sizes through Millwright sizes 2.

It’s common to refer to longer firmer chisels with a socket just as firmer chisels. These will typically have a 30° bevel.

Examples of Firmer Chisels from 1911 Swan Catalog. Tang blade length: 4.5 in. (middle), Socket blade length: 6.5 in. (top and bottom).

Bench

For appearance see the image above. Bench chisel is a description of general purpose chisels like one would use at a workbench. They can be used for light chopping and for paring but aren’t as good at either as their specialized brethren. The handle should be suitable to take a light mallet, but not necessarily capped. Often bench chisels are mid-length tanged firmer chisels. Commonly beveled to 30°, 28° or 27° makes a good compromise of paring and chopping if you don’t have dedicated chisels for those functions.

Butt, short, cabinet & Pocket

Shorter blade, often with a stockier handle.

Butt Chisels [...] are made short, because of the purpose required of them: –fitting in butts on doors.

–White catalog, pg. 7 3

Butt, short, cabinet and pocket chisels are basically the same and you’ll have a heck of a time figuring out which of those the worn, un-handled example you picked up at a garage sale is. If you have the maker’s catalog from the same time period as the chisel manufacture, there’s a chance of distinguishing the pattern of yours against the illustrations. Some makers, especially English, have notable differences between the three patterns.

Of course any firmer chisel used to within the last couple inches of the blade can be used as a butt chisel. In the case of laminated blades, there may not be any hard steel in the last inch or two. Many have a 30° bevel, but can be found set up for paring or chopping as needed. Blade length is less than ~3.5 in.

Examples of Butt Chisels from 1911 Swan Catalog. Tang blade length: 2.5 in. (top and bottom), Socket blade length: 3.25 in. (middle).

Paring

Pushed across the work to slice, not strike or lever. Sharpened 20°-25°. Paring chisels usually start out long. Possibly because their acute edge needs regular honing; using the blade faster. Some prefer a straight-sided paring chisel rather than bevel-edged. Perhaps this has to do with giving more support to the cutting edge, but I’m not positive. Others like a bevel-edge as it gives clearance for pairing in dovetails and like spaces.

Illustration of Paring chisels from a White 1913 catalog. Socket on top and tang on bottom. All blades 8 in.

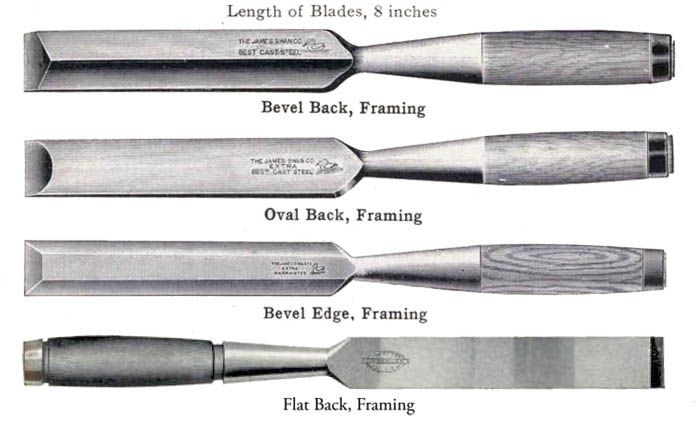

Framing & Deck

Framing chisels are basically larger, longer, and stronger socket chisels. While most modern examples were manufactured as firmers, examples can be found with laminated blades. Manufacturers offered them in a variety of back grindings. They have hooped handles designed for heavy malleting. Blade length appears to be common at 8 in., Deck chisels vary a bit ~5.5 to 6 in, these are intended for the boat-building and coach-making trades. Framing chisels can be found with the gamut of bevels. For general use, honed at 25°-30°. I can’t really understand using one for paring, unless you wanted to fill out a set of pairing chisels past 2 in, but I’m not a timberframer.

The blade, measuring 8 inches in length, is of extra heavy cross section and is made of solid steel. The socket is of heavier-gauge tubing and larger and longer than that required on the comparably light firmer chisel.

–Greenlee, pg.54 4

Illustration of three Swan and one Greenlee framing chisels. Cuts from 1911 Swan catalog and 1941 Greenlee catalog.

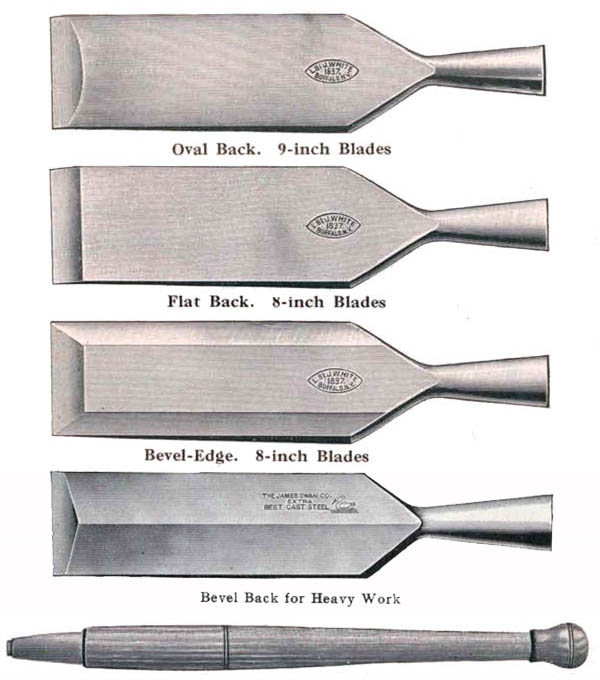

Slick

Slicks are wide socket paring chisels, generally built to the same toughness as a framing chisel. Due to the large volume of steel these are often laminate but some solid (firmer) examples are known. As they are mostly used for paring, they should be beveled 20°-25°. Slick widths usually fall between 2.5 in. and 4 in. The distinctive feature of a slick is its long baseball-bat shaped handle.

Illustrations of Slicks from White 1913 & Swan 1911 catalogs. Oval back is laid steel, others solid cast steel. Bevel-back from Swan came 10 in. long.

Mortise

Mortise (also: mortising, mortice) chisels are used to make and clean out mortises. The blade is thicker than a bench chisel. Like framing chisels, they are made with both laminated and firmer blades. Mortise chisels are all designed to be struck by a mallet and should withstand prying. Many have hooped or at least capped handles. These chisels are usually sharpened to 30° or greater bevel.

English mortise (Pig Sticker)

So named because they look like butchering tool. These are thick bladed with a large bolster fitted over an oval handle.

Sash

Or Sash-Mortise chisel. These are lighter in construction than the above but sturdy and suitable for furniture and carpentry. They generally come with a tang and a more refined, turned ‘carving’-style handle. Modern examples are often socket firmers with no edge bevels, and perhaps slightly thicker.

Registered

Some are using the term ‘registered’ to describe flat-top chisels without edge bevels.

However, it seems ‘registered’ may factually refer to the construction of the handle, being previously registered with the British patent(?) system. These all seem to be tanged with a strong ferrule and a hoop on the handle.

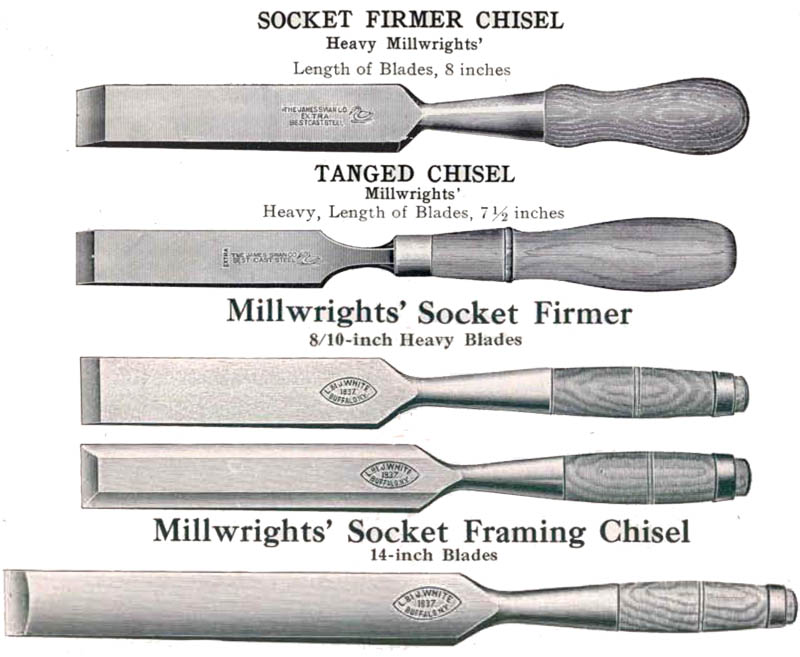

Millwrights’

Millwrights’ chisels are longer, stronger or both forms of most chisels. There are Millwrights’ socket firmers, tang firmers, framing chisels, and socketed chisels exclusively called Millwrights’. White offered their Millwrights’ socket firmers up to 14 in. long. Intended for heavy work, a durable edge of 30° is expected but uses for a finer edge are aplenty. It’s unclear if there is any real difference between millwright’s and framing chisels. They both seem to have a wide range of features, lengths, durable construction, and a similar use in their trades.

Illustrations of Millwrights’ chisels from Swan (top two) and White (bottom three) from their 1911 and 1913 catalogs, respectively.

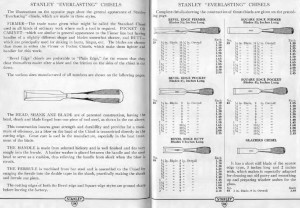

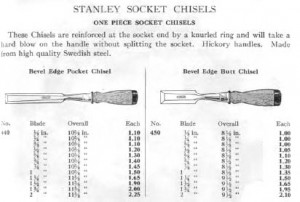

Stanley Chisels

Since so much of the old tool world revolves around Stanley, I realized I should add a section addressing their line. The scan of their 1934 catalog seemed as good as any explanation I could give and has been reproduced below, sans ‘Stanloid’/plastic handle models.